Tracing the History of Japanese Family Crests through Iroha-biki Monchō

In the Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections (located in Fisher Library), there lies a small red book, Iroha-biki Monchō いろは引紋帳 / 田中菊雄編輯 (EA 2280.8 1), whose title translates to ‘A Complete Book of Crests Arranged in ABC Order’. Published in Tokyo in 1881, this dense volume is an index of Japanese heraldic crests dating back to ancient times.

The book pages are made from single-sided sheets of washi paper, folded in fukuro-toji (pouch) style, where the sheet ends are tucked into the binding. The binding follows the tetsuyōsō (‘multi-section’) technique, a format commonly used in Japanese bookmaking of that time.

The story of Japanese crests

Even a casual observer of Japanese culture will notice the ubiquity of crests, particularly family crests. Monchō (crests), and more specifically kamon (family crests), have played an important role throughout Japanese history as emblems of status and power. But that role has changed considerably since they first appeared during the early Heian Period (794-1100s).

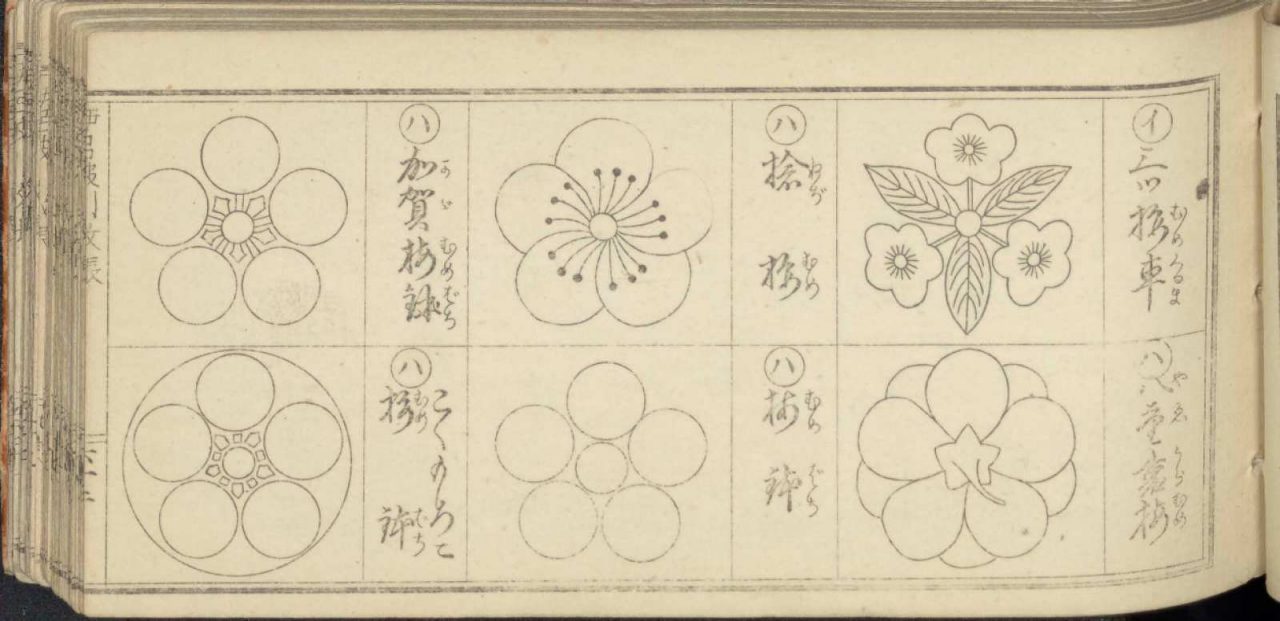

Originally used by noble families to distinguish property as well as to decorate clothing, early kamon served aesthetic and courtly purposes, and were often constructed from natural iconography such as flowers and wildlife (Okada, p.13-14).

By the Kamakura Period (1192-1333), as military families gained power, their function grew to suit martial purposes. In particular, decorating battle banners with kamon helped distinguish allies from enemies during combat (Okada, p.15-18). By the 14th century, military crests had flourished, with a plethora of new designs having been imprinted onto armour, weaponry, tents, flags and other items.

A book from a time of change

In the Edo Period (1603-1868), Japan was unified under a strong and centralised military regime, the Tokugawa Shogunate. This period of relative peace saw the redefinition of old crests and the emergence of new ones. Samurai occupied the top of a strict social hierarchy, and while kamon were no longer functional in a military sense, they remained central to samurai identity, which was deeply tied to pedigree. They were, for example, displayed by the companies of feudal lords (daimyō) while in transit or during visits to the capitol of Edo (modern-day Tōkyō) (Okada, p.21-22).

It was common for members of all statuses to look up crests in an annual ‘military directory’ called Bukan to assess the appropriate level of etiquette they should display to visiting warrior dignitaries (Okada, p.22; Berry, p.239). Samurai, nobles, and aristocrats ensured their kamon were displayed on temples and shrines to which they had provided funding. Merchants displayed their crests on shop signs and their employees’ uniforms (Okada, p.94), a branding method still practiced today. For example, this Edo Period scroll from the Tokyo National Museum depicts shops with kamon logos in Kyōto.

Iroha-biki Monchō was compiled in the early Meiji Period (1868-1912), when Japan was undergoing rapid modernisation and social restructuring. The ‘premodern’ Edo Period, however, remained vivid in living memory. At the time of publication, the Edo status system had been abolished and domains previously controlled by daimyō were merged into imperially governed prefectures. Iroha-biki Monchō was released a few years after the complete dissolution of samurai economic privileges and amidst the increasing elimination of aspects of samurai identity such as the right to wear swords in public (Gordon, p.64-65). Despite these changes, the Edo class system lingered both materially – crests were, and still are, widely visible in Japan – and psychologically, with former samurai referred to as shizoku out of respect for their former status. The compiler of this book, Tanaka Kikuo, is himself identified as a shizoku on the back page.

A glimpse of Iroha-biki Monchō

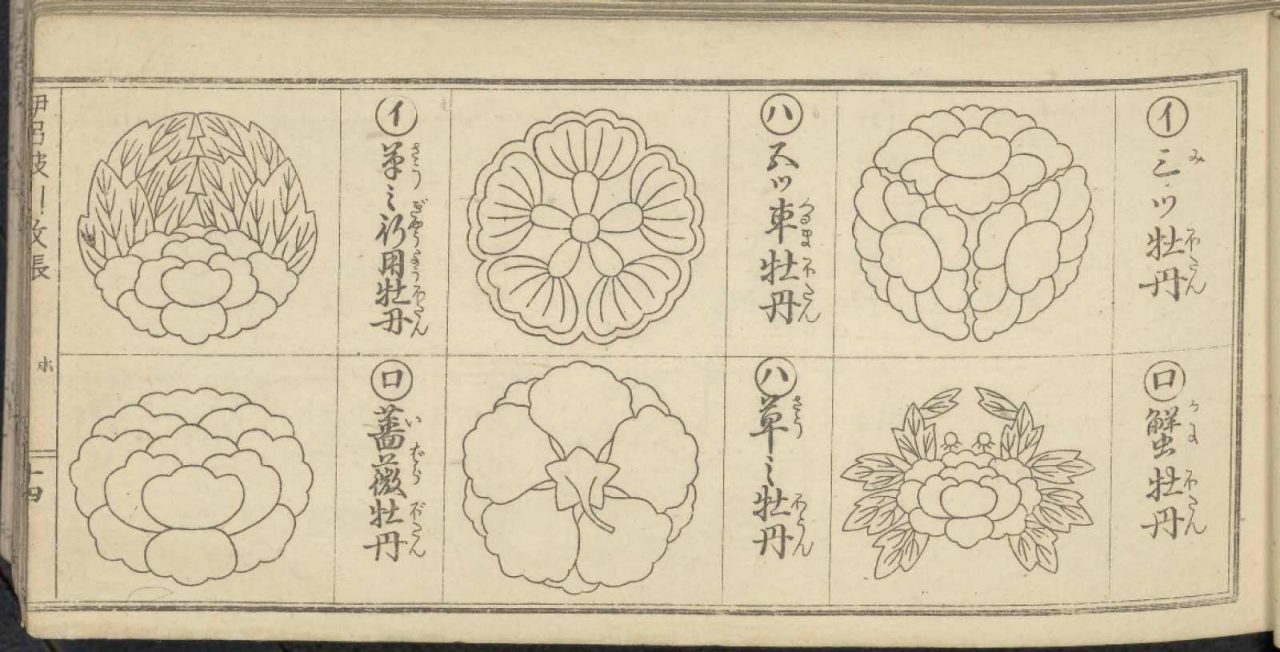

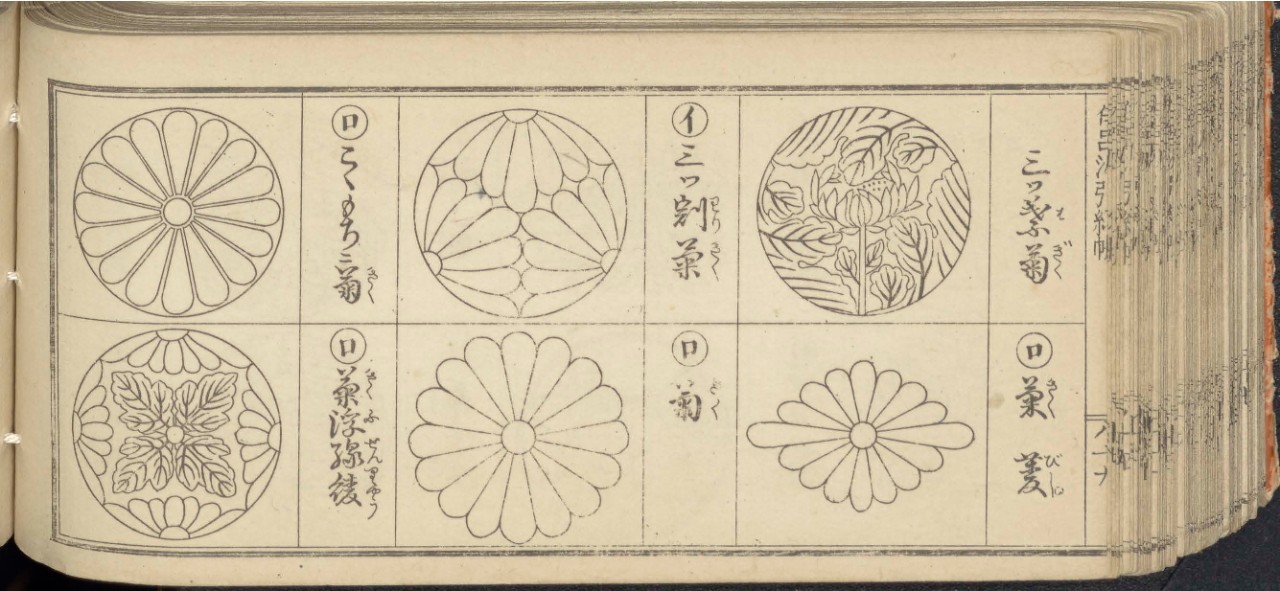

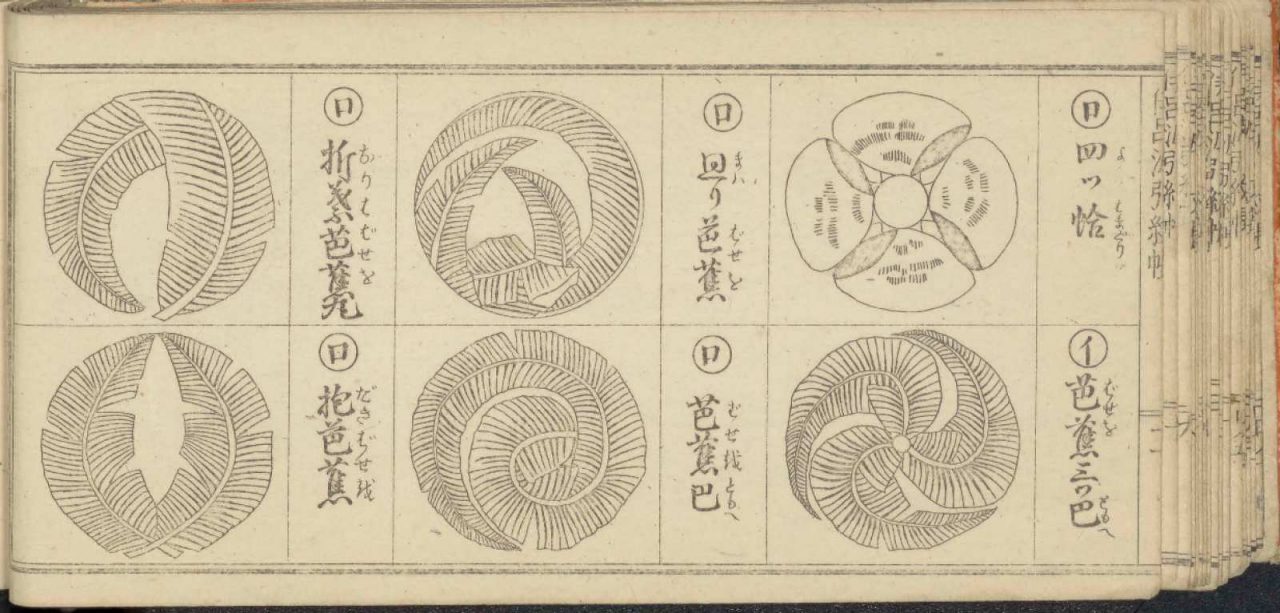

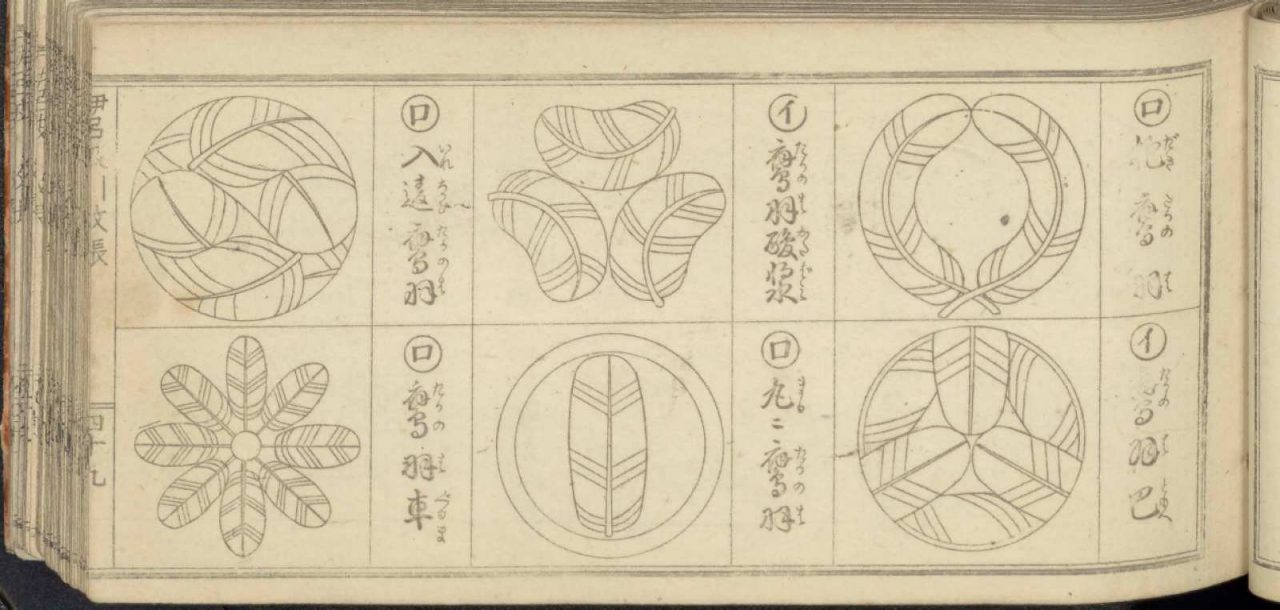

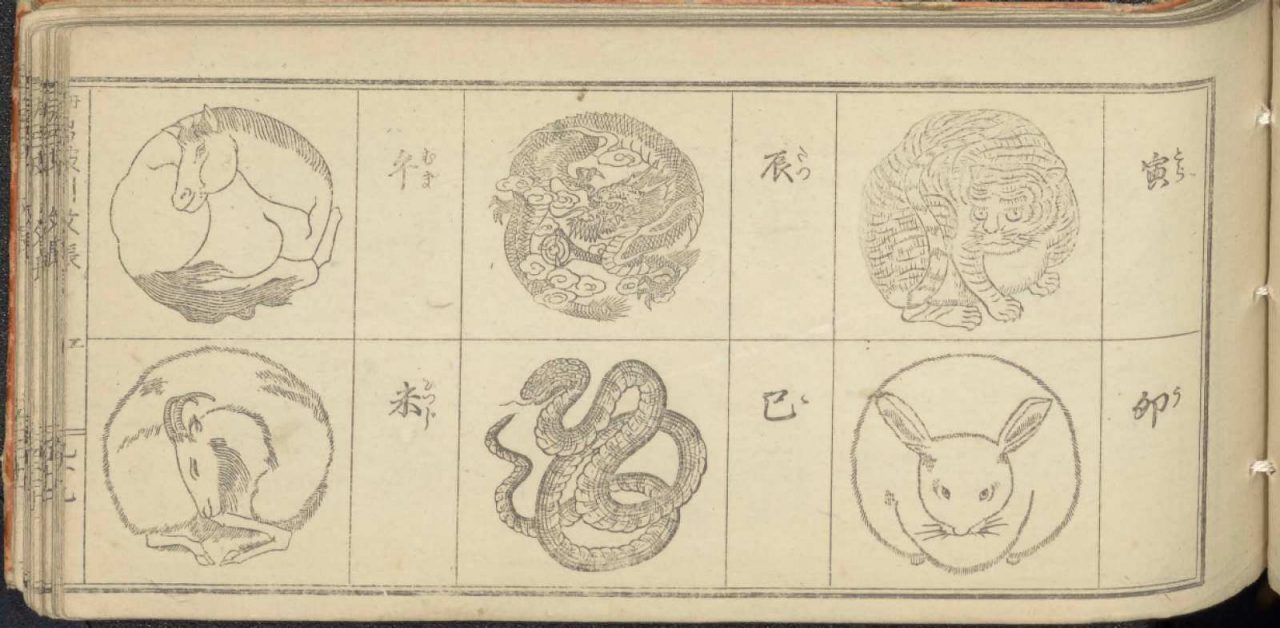

The extraordinarily wide range of visual motifs can be seen in the pages of this volume: circular crests range from depicting simple geometric shapes, to more complex motifs such as flowers, insects, celestial bodies and zodiac animals. There are even some quirky, aesthetically-oriented crests that fuse these elements together, such as a crab made of peonies (as pictured here)!

The book’s crests are organised by motif, and the motifs are arranged alphabetically according to Japan’s traditional Iroha alphabetisation system. The front matter does not seem to emphasise the emblems as ‘family crests’, but rather gestures to crests in general.

The text beside each emblem imparts a neutral account of its design – for example, ‘facing butterflies’ or ‘three fans in a circle’. For a tradition deeply rooted in political and social power dynamics, as well as high culture, this detached description seems a little out of the ordinary. The book’s taxonomical style, however, reveals much about the changing landscape of Japanese culture and society in the Meiji Period.

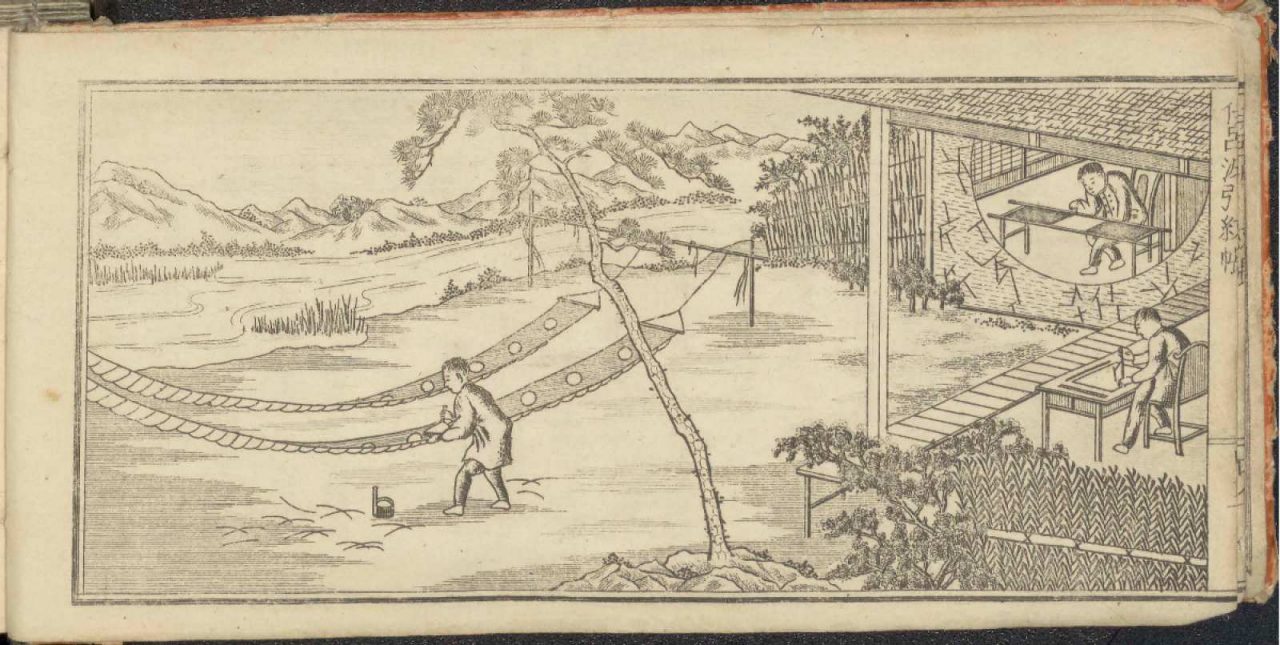

Many of the book’s inclusions suggest that it was instructive to craftspeople imprinting crests onto kimono, an art that coincided with the proliferation of crests but has been in decline since Japan’s industrialisation. Most obviously, an illustration following the introductory pages depicts monsho uwaeshi, crest artisans, transferring kamon onto fabric (pictured at top of this article).

The figure on the middle right-hand side can be seen using a specialised bamboo compass, a bun-mawashi, to draw perfect circles as part of a kamon’s design. The figure closest to the centre of the image can be seen applying an ink wash onto fabric, printed onto which are kamon covered by resist paste. The stooped position of the top right figure, along with his lack of tools, suggests that he may be performing a quality check. The fact that these craftsmen are using western-style chairs is a significant detail which reflects Japan’s uptake of western culture and aesthetics during the Meiji Period.

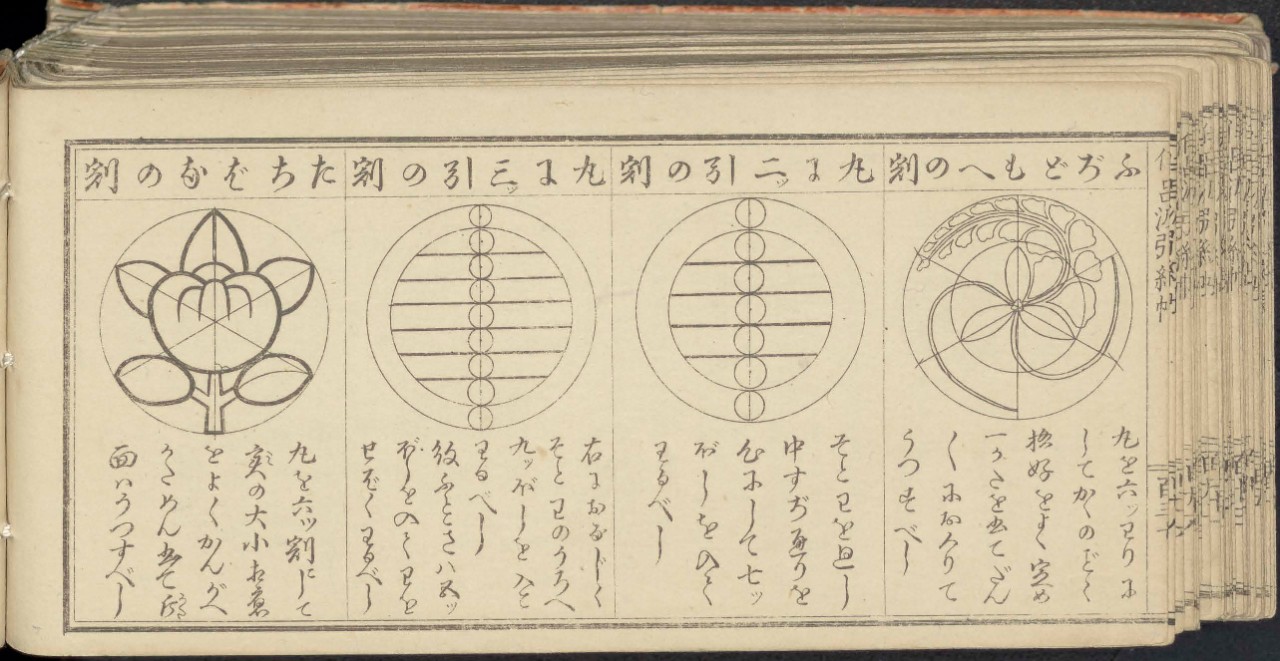

A section near the end of the book, furthermore, shows how different crest designs should be carved and imprinted: detailed diagrams show the geometric precision essential to kamon design.

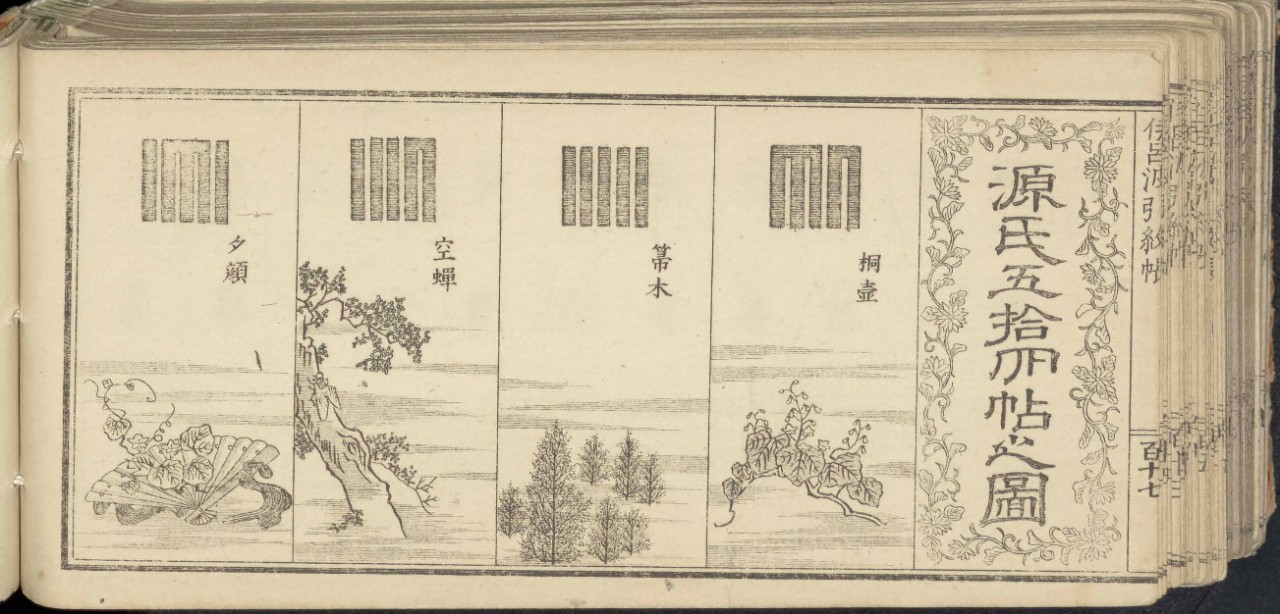

The book also contains a section dedicated to crests representing each of the 54 chapters of the Tale of Genji, serving as further evidence of upper-class traditions that had been cultivated around these emblems.

A pioneering literary romance written in the 11th century, the Tale of Genji heavily influenced Koudou, the art of incense appreciation, with the incense-comparing game of Genji-kou played by aristocrats during the Edo Period. Players would try to distinguish different scents and indicate their deductions using Genji-kou-mon, a range of specialised symbols corresponding to the different chapters (Louis Frédéric, p.237).

The book’s focus on crests as a craft rather than a political tool is significant considering the changes occurring in Japan during the early Meiji Period. Seated amidst a context of globalisation and increasing western influence, it is quite possible that this book was an attempt to preserve an aspect of samurai culture whose tradition was in sudden decline. It may also be seen as an expression of pride in a unique facet of Japanese culture during a time of rapid socio-political change. Thanks to Tanaka Kikuo’s compilation, and the publishing craftsmanship of his non-samurai collaborator Matsuzaka Hanzō, Irohabiki Monchō provides a detailed record of an aspect of Japanese material culture that is widely recognised yet seldom discussed in detail.

While crests are no longer used for official purposes, they are a living presence up and down the Japanese archipelago, and their refined visual sensibility continues to be reflected in logo designs the world over.

Meanwhile, the traditional craft of printing and designing kamon is finding new ways to thrive in contemporary art (Lucas). Though modest in size and illegible except to those with detailed knowledge of Classical Japanese, Irohabiki Monchō can engage any viewer with its accessible yet exquisite designs. The timeless aesthetic appeal of the crests it records, along with what they can teach us about Japan’s cultural history, makes it a treasure of the Library’s collection.

Access this item

View online

View a fully-digitised version of this item online

View physical copy

Make a request to view this item through the Library catalogue, under "more options".

This story was written by student Jemima Rice, as part of the course JPNS3002 Classical Japanese.

Thank you to Leen Reith and Emily Kang from the Library for the opportunity to write this article. Thank you to Dr Matthew Stavros and Dr Matt Shores for their invaluable guidance in interpreting this object and its history.

Works cited

- Berry, Mary Elizabeth. “Public Peace and Private Attachment: The Goals and Conduct of Power in Early Modern Japan.” The Journal of Japanese Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, 1986, pp. 237–71.

- Gordon, Andrew. “The Samurai Revolution.” A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. Oxford University Press, 2003, pp. 61-76.

- Frédéric, Louis & Roth, Käthe. Japan Encyclopedia. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Lucas, Anne. “The Art of Kamon: How one father-and-son team is transforming the traditional culture of creating Japanese family crests into an in-demand modern art form.” Tokyo Metropolitan Government publication,n.d. [link].

- Okada, Yuzuru. Japanese family crests / by Yuzuru Okada. Board of Tourist Industry, Japanese Government Railways, 1941.

Contact

Please email enquiries to cultural.collections@usyd.libanswers.com